Day 2 Report

Freedom of expression and privacy | 3:00 - 4:30 UTC

👤 Sanhawan Srisod

Session details:

This session is aimed to explore the laws protecting freedom of expression across the South Asian region, while also examining the restrictions placed on this right within different legal systems. Participants will look closely at laws addressing hate speech, sedition, blasphemy, and defamation in their regional contexts. The session will further provide a brief historical overview of these laws and restrictions, tracing how they continue to surface in both offline and online spaces today.

- Broadly, what are the provisions that cover freedom of expression in international human rights law and national legislation in South Asia?

- Restrictions on FoE - what does international law say, and how does it compare to the kinds of restrictions we see in South Asia (hate speech, sedition, blasphemy, defamation and mis/disinformation etc.)?

- What kinds of laws are being passed in South Asia in relation to freedom of expression online? How does this differ from how FoE is regulated offline?

- What is the role of platforms with respect to freedom of expression online? What impact does the current policy approach towards platforms in South Asia have on FoE online? What needs to change?

Notes:

Introducing International Commission of Jurists (ICJ)

ICJ is an international NGO based in Geneva, consisting of a group of lawyers that aims to promote the rule of law according to human rights standards.

In 2019, ICJ released the report Dictating the Internet: Curtailing Free Expression, Opinion and Information Online in Southeast Asia (2019) which noted a worrying trend on legislations and frameworks regarding regulating the internet. Since the release of the report, there had been no changes, if not worse, in such regulations. In the past 5 years, many laws in SEA countries had shown a chilling impact on FoE, with new laws revolving around regulating AI looking similar to previous cybersecurity laws.

Following the report, ICJ had also released various country-based reports, including Cambodia 2020, Vietnam 2020, Thailand 2021. 30% of the reports highlighted the legal frameworks that were further accelerated to curb the Covid-19 pandemic.

Other reports produced are:

- Singapore’s Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 - to what extent it comprises the human rights principles

- Counterterrorism and Human Rights in Philippines, 2022

ICJ had also issued statements, including on Indonesia’s ITE Law revision’s threat towards FoE.

Currently, ICJ is working on developing The Global Principles, which looks into existing international law and standards - both UN treaties and regional instruments - and how it should be interpreted, applied, and enforced in the digital space, in the spirit of progressive development. The project looks at various international standards, including criminal law, to regulate the digital challenges that arise especially with the emergence of AI, which has caused rapid changes in tech and digital spaces.

The Global Principles contains 35-37 principles, split into 5 Scopes:

-

- General Principles

- State obligations

- Corporate responsibilities

- Remedies and Reparations - Recognising the types of harms, the potential remedies and access to acquire the solutions

- Accountability - mainly focusing on an individual’s accountability on violations in the data world, and the judiciary oversight that is eligible

The project was first launched in June 2025 and aims to be finalised in mid 2026.

The drafting of the Principles is to be accompanied by advocacy guidance or commentary to ensure that this can be a useful and practical toolkit.

Human Rights Laws on the Online and Digital World

In general, most of the human rights laws were created after WW2 and had no considerations on the digital space at the time. With the evolution of the digital space, the conversation mostly revolves on which human rights laws that are traditionally applied offline could be converted online, as it is more complicated in the latter. With more government services being transferred online, there is a higher urgency for every individual to remain connected in order to gain access to certain rights.

Certain rights that are often being interchanged in both spaces are:

- Freedom of Assembly: could be protected offline, and should be online as well.

- Right to Health: Revolves around access to the best quality of healthcare service. Many services are now utilising telemedicine platforms and digital health options.

- Right to Development - Indicates the protection of natural resources and economic development. However, it is more vague and ambiguous online

- Freedom of Opinion and Expression - should be protected

- Freedom of thought, conscience, and religion - UN Expert confirmed that it should be protected

- Right to Privacy - definite.

The pandemic spurred several other new trends as many services were forced to be online:

- Right to standard of living/access to food

- Right to education

- Right to work

- Rights to equality, equal protection of the law, and discrimination

International Instruments on Freedom of Expression: ICCPR

Most SEA countries are part of the International Covenant on Civil and Party Rights (ICCPR). Countries that do not officially rectify this are still bound to the ICCPR’s general rules and practice.

Customary international law - ‘international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law’, which means there must be a general and consistent practice by States, while there an agreement exists among them that the practice is acceptable. This also applies to certain laws that are not necessarily rectified by all, but most countries should abide by it. One of the most famous instruments that has achieved this is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including FoE. However, it is important to bear in mind that the UDHR is an old instrument.

- Article 13 - right to freedom of movement

Freedom of Expression is based on Article 19 of ICCPR.

- Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, through any other media of his choice.

In 2011, the UN released a General Comment NO.34 to the Article 19, which includes FoE protection online via “protecting in all online and audio-visual form” .

Requirements for restrictions of human rights online

There are three conditions where restrictions may occur:

- Normal times - human rights treaties allow certain limitations on human rights

-

- Restrictions under Art 19 of the ICCPR

-

-

- “... subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: (a) for respect of the rights or reputations of others; (b) for the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public); or of public health or morals”

- “Must conform to the strict tests of necessity and proportionality"

-

- Restrictions under Art 20 of the ICCPR

-

- “Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law.”

- “Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.”

- Emergency situations that threaten the life of the national (e.g major natural disasters such as severe floods or earthquakes; public health emergencies such as Covid-19)

- Wartime

Non-compliance trend - patterns of abuse reflected in laws during normal time

Referring to the FoE restrictions under Article 19 of ICCPR:

- “... subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: (a) for respect of the rights or reputations of others; (b) for the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public); or of public health or morals”

- “Must conform to the strict tests of necessity and proportionality"

To understand if the restriction is legitimate, one should conduct the 4-part test (to prescribe restrictions):

- Legality: prescribed by law while ensuring that there are clarity in its regulations

- Legitimate purposes: pursue a purpose recognised as legitimate under human rights treaties

- Necessity: necessary for achieving that purpose (because there are not other human rights framing to conduct it)

- Proportionality: proportionate (ensure that the law is on equal level with the harm. For example, the law of defamation should not entail imprisonment or criminal penalties)

- + non-discriminatory

Whereas restrictions under Art 20 of the ICCPR states that:

- “Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law.”

- “Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.”

To define incitement, a 6-part test called Rabat Plan of Actions is used for expressions considered as criminal offences:

- Context

- Speaker

- Intent

- Content and form

- Extent of speech act

- Likelihood and imminence

In Meta, one can file a complaint to The Oversight Board who will look based on the Rabat Plan of Actions. One specific case is that the Oversight Board has overturned Meta’s decision to leave up a video of the Cambodian Prime Minister’s threat towards his political opposition.

Laws with FoE Restrictions and Case Studies

Laws that commonly restrict FOE even in the online sphere are :

- Laws protecting reputation (defamation)

- Laws on national security and public order

- Laws regulating online information

- Laws aimed at controlling the spread of ‘disinformation’

- Laws regulating telecommunication

The common theme is that most laws offer vague and overly broad provisions such as ‘false information’ (against Legality). Some laws also fail to clarify terms such as “public order” “national security” (legality & legitimate aim). This poses a question on who gets to define false information, and against whom. However, despite the ambiguity, such laws would impose severe penalties such as imprisonment e.g. some acts under A20 (Proportionality).

One participant mentioned that “these laws in the region are often colonial era laws that do not get updated with any recent human rights development or recommendations, which puts a challenge as these are systems that were never designed with the realities of the region and today’s world.” The slow or refusal of improving such laws in accordance with recent updates and research also creates tension that often jeopardises civil society and actual public interest.

Another pointed out that such ambiguous provisions, more often than not, diminishes public confidence in the performance of the government.

Case study 1: Computer-Related Crime Act (2007) - Section 14 - Thailand

Vague and broad legality and legitimate aims: The definition of ‘national security’, ‘public safety’, ‘economic safety’ is highly dependant on the authority

Instances where this law has been used:

- A BBC journalist faces defamation charges in Thailand, in which the ‘National security’ could be used even on a municipal level.

- A HRD who posted an incorrect location for a mosque, and quickly corrected it in 30 minutes. But still gets charged as the post was detected by the military.

- Entertainers, media, or songs that criticises the authority

While most of these cases are often dropped after judiciary oversight, the affected individual(s) and their resources are still largely impacted.

Case Study 2: Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 - Singapore

Vague and broad legitimate aims: Lack of definition on the ‘false statement of fact’; security; public health, public tranquility, public finances, friendly relations with other countries, influence the outcome of an election

Case Study 3: Article 27 (Philippines)

Contents against propriety / contents of affronts and/or defamation

Case Study 4: Cross-border jurisdiction

Recently an Australian journalist was recently indicted for alleged Malaysian government defamation following a complaint from the Malaysian MCMC, and was filed a complaint via the Malaysian Embassy in Thailand. The question is which jurisdiction’s laws apply when the alleged “defamation” originates from published content accessible across borders.

It is worth noting that Defamation is a common weapon in the political sphere. This tactic suppresses any political opinion, which is used either on opposing political actors or even on common public individuals. This causes a decrease in confidence among the public to express their opinions.

Restrictions during Emergency Situations or Wartime

Access to human rights in the digital space during natural disasters can be disrupted by the infrastructure damages caused by the occurrence, which could lead to users having lack of access to important updates and information. It would also cause low capacity on getting access to support and resources.

However, certain states have conducted drastic measures such as internet shutdowns, disrupting mobile signals, or platform blockings to reduce any coverage on potential protests, dissent or their neglect towards counteractive policies.

Some rights may be derogated from, but only if the measures:

- Strictly required by the exigencies of the situation exceptional and temporary, and it should be removed once the situation has improved

- Not inconsistent with the State’s other obligations under international law

- Do not involve discrimination

For example, in Myanmar: The Telecommunication Law 2013 contains a provision “For the duration of the public emergency, direct any licence holder to suspend telecommunications”. This could create legitimate aim concerns as the “duration” and the “public emergency” are not well-defined, and it could be extended even if the conditions have improved.

Concluding thoughts:

Troubling State responses include:

- Enacting overbroad criminal laws

- Introducing laws that lack precise definition

- Granting unchecked

Corporate Responsibilities:

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs)

- Advertisement-driven business model - profit driven, often push posts that incite hate and bigotry for high engagement.

-

- Myanmar: Facebook systems promoted violence against Rohingya

- Thai influencer profiting from the Border conflict with Cambodia

- Inadequate content moderation

-

- Meta is ending their third-party fact checking mechanism which involves hiring human fact checkers, to move to the community note model. The latter could run into some risks as there are no proper guidelines on doing so, with the vague morality across the public

- Opaque policies and practices

- Lack of accountability

Tech companies shall:

- Review their business models

- Content moderation practices shall be consistent and sufficiently resourced, with human-in-the-loop safeguards

- Adopt clear and easily accessible policies aligned with IHRL

- Conduct regular human rights impact assessments

- Publicly report on government requests

- Establish effective remedy mechanisms for wrongful takedowns

Reflection Questions:

- Most of the issues revolve around the definitions of the term being used. Would it be helpful if the terms are further expanded (thus binding) in law, or would that result in further complications?

- Who has the authority to define such terms? What avenues needed to imagine and realise alternative solutions beyond the agendas set by big tech, the state and other powerful forces?

- Cross-border jurisdiction: recently an Australian journalist was recently indicted for alleged Malaysian government defamation following a complaint from the MCMC, and was filed a complaint via Malaysian Embassy in Thailand. Which jurisdiction’s laws apply when the alleged “defamation” originates from published content accessible across borders?

Privacy, surveillance and data protection | 5:00 - 6:30 UTC

👤 Jam Jacob

Session details:

In this session, participants will learn to examine the different facets of individual privacy in the digital age and the regulations designed to protect these rights. They will investigate the impact of emerging technologies on decisional privacy by considering the various forms of surveillance currently deployed in society alongside the enabling legal frameworks. This session will further focus on the rise of surveillance-related policies and their implications for the protection and promotion of digital rights.

- What is privacy in the digital age and why is it important?

- What are the ways in which the internet and other digital technologies are being used to infringe privacy and engage in surveillance?

- What are the legal and regulatory frameworks in south Asia that protect privacy, including data protection laws? What are the challenges and gaps?

- What are the ways in which legal frameworks in South Asia are being used to enable surveillance?

- What is the impact of such policies on freedom of expression, assembly and association and other rights, esp for marginalised groups?

Notes:

Objective:

- Learn to examine the different facets of privacy in the digital age and the regulations designed to protect these rights

- Investigate the impact of emerging tech on privacy and other digital rights by considering the various forms of surveillance deployed today alongside the enabling legal frameworks

Privacy and Data protection

Definition of Privacy:

As far as privacy is concerned, it’s difficult to come up with a universally accepted definition due to many factors that influence the individual and society’s notion of privacy.

European Court of Human Rights, Niemietz v Germany (1992) stated that the notion of private life is a broad one, not susceptible to exhaustive definition.

The first definition on privacy was by the right to privacy was first defined as ‘the right to be le(f)t alone’ (Warren and Brandeis, 1890 Harvard Law article), which is the most cherished of freedoms in a democracy.

Participants were asked to define their understanding of privacy, which includes:

- Control over personal information, including location and online activities, and the power to decide who can access your data and how it’s used

- Our authority and independency to protect essential data and information related to interests and rights

- Right to decide who has access to us, to be left alone, and how these terms can be fluid and dynamic to fit an individual’s needs

- Ability to control what to share, with whom, and under what conditions

- With the rise of AI and LLM, many platforms have manufactured our consent to feed our information and data to their LLM processes, and it is difficult to opt out. Many BigTech companies complicate the processes by hiding their privacy settings.

Right to privacy:

The right to privacy is commonly understood as physical space free from interruption, intrusion or embarrassment, or accountability. There is an interest in human personality; it protects independence, dignity and integrity.

Previously, many legislations aimed to prevent people from invading physical and information privacy. But as technology advances, the line of privacy becomes blurred, along with its legitimacy. For example, prior to the heavy use of the digital space, trespassing physical properties and accessing confidential documents were seen as invasive. However, although wire-tapping phones or phonelines are inherently intrusive techniques, they have played huge roles in revealing and uncovering some important conversations and information.

Our intricate relationship with technology needs further prodding, especially in defining the boundaries, as “Privacy in an age of primitive technology was largely a function of inefficiencies in technology in monitoring and searching.” (Jeffrey Rosen).

Aspects of Privacy

- Privacy of communications - emails, messages and telecommunications

- Bodily privacy - from certain invasive procedures, physical space. For instance, airport scannings could lead to feeling discomfort, hence the need for some regulations on the procedure.

- Territorial privacy - Rules governing the proper conduct on physical surveillance such as by private investigators, law enforcement agencies, CCTV cameras and its locations (in restrooms or rental homes)

- Informational privacy

Example: One participant shared that privacy of communications and informational privacy could affect health and reproductive health centers, as affected women may need access to get their right to decisionmaking on accessing the contraceptives needed.

International Policy Landscape on Privacy

There are two important international instruments on privacy, which are:

1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 12 (UDHR is a law, not a treaty. Not necessarily binding):

- “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.”

1966 International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights, Article 17: a treaty, binding

- “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.

- Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

ICCPR Signed: Cambodia, Philippines

ICCPR Ratified: Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, PH, Thailand, Timor Leste, Vietnam

Not signed nor ratified: Brunei, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore

- Malaysia - goes against national constitution that protects the Malay Majority rights

Other international laws can be found here (slide 11).

Permitted Limitations:

The right to privacy is not absolute, and the infringements/intrusions must not be arbitrary or unlawful. It should be tested against these 4-part tests:

- Must have a legal basis

- Must have a legitimate aim (national security, public order, public health, morals)

- Necessary/necessity

- Respect the principle of equality/proportionality

For example, if the surveillance is conducted according to selected legal basis, then it is permitted. The surveillance method could also be proven necessary if the information could not be retrieved through other means.

Constitutional Guarantees listed on slide 13.

Comparing UDHR and Vietnam’s constitution, which shares the same principles:

Data Protection

This means the individual has control over one’s personal data.

Data protection vs data privacy: In many cases, these terms have been used interchangeably. There are many arguments on the perceived distinction between these two concepts, and the closest that is suggested by the RP is by looking where the user is coming from. If you are the rights holder of your own information, you may call it Data Privacy.

But if the individual is acting as a person who has authority over a number of data (Controller, Duty Bearer), then it would be referred to as Data Protection.

In the Philippines, the Data Privacy Act 2012 is mostly based on the EU Data Protection Directive 1988 (the predecessor of GDPR).

Data protection vs information security: while data protection looks at personal and individual data, information security refers to a larger scope of data and information. This includes data that are not necessarily considered under privacy (including weather, economy, etc).

- Tasks under Information Security:

- Ensure the confidentiality and backup copies are still accessible and available

- To ensure the information remains accurate, up-to-date, integrity is intact

- Tasks under Data Protection/Privacy:

- Similar as IO, but extra concerns with regards to the rights of the data subject, privacy principles, security/safeguarding from intrusions

The earliest discussion on information technology occurs in the 1960s, coinciding with the development of computers and faster processing of data. States began to worry that these systems, if left unchecked, would lead to harm.

- Hesse, Germany - first known modern data protection law

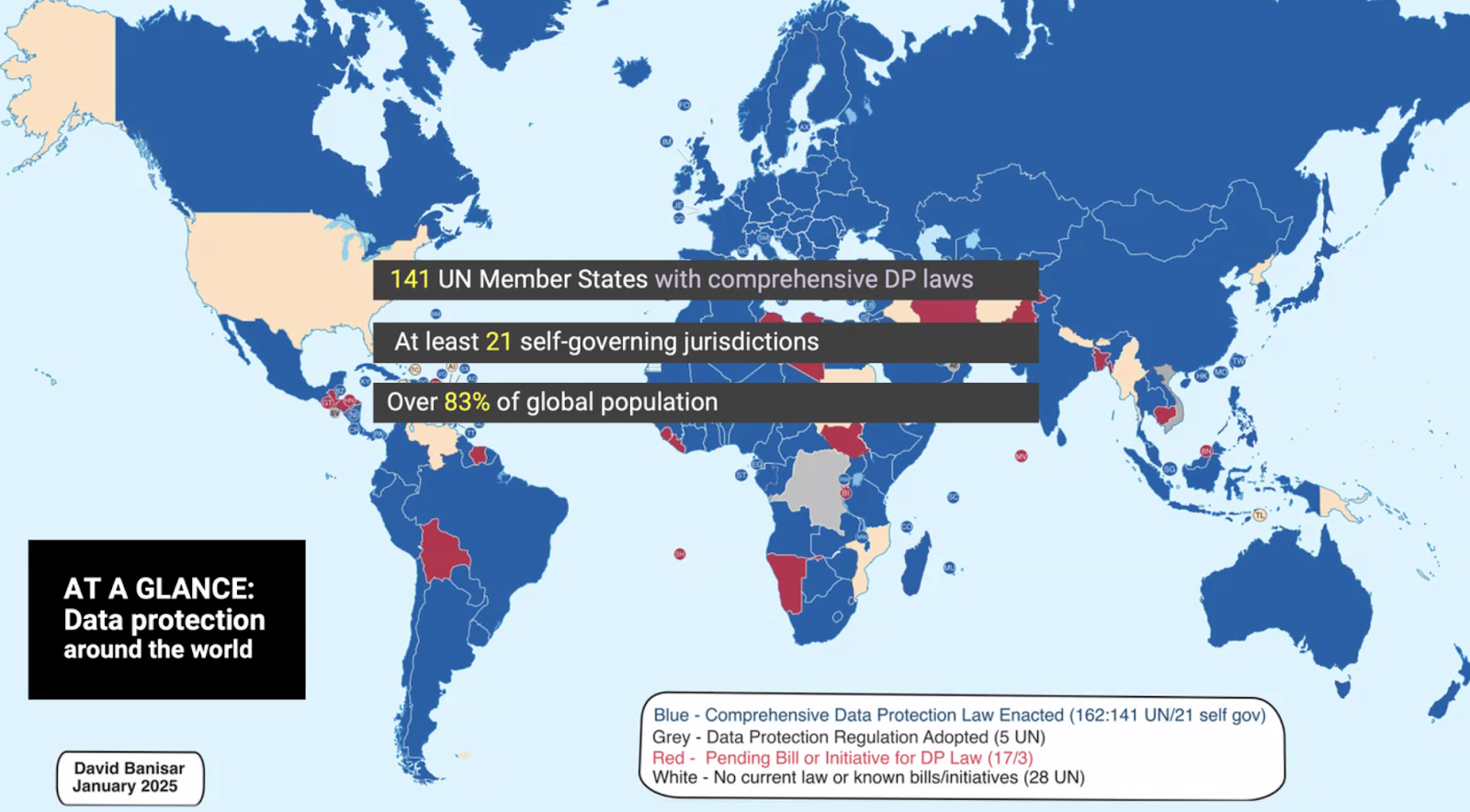

International Policy Landscapes on Data Protection:

- Fair Information Practices Principles (1973)

- OECD Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (1980, 2013) - Most laws follow this guideline

- COE’s Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to the Automatic Processing of Data [No. 108+] (1981, 2001)

- EU Directive on Data Protection (1995) - influenced the Philippines

- APEC Privacy Framework (2005, 2015) - has less influence compared to EU Directive

- EU General Data Protection Regulation (2016) - most influential and regarded as the standard of data protection

Slide 16-17, which includes the SEA countries’ Data Protection Laws and their year of enactment:

* Myanmar’s Data Protection Regulations took reference from their Cybersecurity Laws

** Only Cambodia has no Data Protection Law.

*** Zana mentioned: Malaysia’s Data Privacy Law is still limited to PDPA that only regulates how personal data is handled by organisations in commercial transactions, and does not effectively address other aspects such as doxxing. Even when doxxing falls under laws such as PDPA + CMA + CCA, these laws do not expressly provide proper avenues to address these crimes because CMA and CCA were enacted before cybercrimes became more relevant.

Regional Laws and Mechanisms:

- ASEAN Framework on Personal Data Protection (2016) - high level principles that are supposed to guide ASEAN members, such as consent, access, security, safeguards over borders

- To build/facilitate transferability across regional legislations

- ASEAN Digital Data Governance Framework (2018)

- Data protection, data flow, security

- ASEAN Model Contractual Clauses for Cross-Border Data Flows (2021)

- Support a trusted harmonized ecosystem that enables a robust regional digital system. Cross-border data transfer is discouraged, but it is allowed according to certain requirements. These are contract templates that organisations can use to offer enough protection for the data transfer within ASEAN

- ASEAN Data Management Framework (2021)

- APEC Privacy Framework (2004, 2015)

- Global CBPR Forum (2023) - builds upon APEC’s certification on cross-border data system

One participant pointed out that the current geopolitical context also shows that such data is also being used for international trade. As part of the tariff negotiations with the US, the Indonesian government initiated that both countries will finalise commitments to digital trade, services and investment, including the ability to transfer personal data out of its territory to the US. This is their attempt to navigate around the EU's GDPR.

Emerging Tech, Enabling Laws and Impact on Digital Rights

Recall: privacy-technology relationship

In the 21st century, we witnessed rapid development in tech capacity to intercept and process communications; major drop in data retention costs. There are various mechanisms in trying to protect data via encryption.

These are the list of emerging tech and laws that are troubling:

- AI-enhanced CCTV & facial recognition in ‘safe city’ projects

- Example: Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore

- Commercial spyware deployed by law enforcement and other government agents

- Academics, civil society in other places are being surveilled by the Pegasus tool, which enables users from another country or region to access their files

- Example: Thailand

- Social media monitoring & data-access rules, including using AI tools

- Vietnam - a law that requires platforms to monitor social media content and store data collected from the citizens within the jurisdiction of the government

- Many other countries are beginning to take note of this. This could also lead to privacy and information leak

- SIM registration & large-scale identity databases, dangerous with the constant data leaks to companies, and intrusive surveillance by governments

- Most countries in SEA

Examples of Enabling Laws: Domestic (slide 22-25)

There are laws that facilitate the usage of these technologies. These slides looked at Myanmar, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Myanmar

- Cyber Security Law (2013, 2021)

- Requires digital platforms to retain data for 3 years and turn it over upon mere request by any military-controlled authority

- Ideally, state governments need to apply to request.

- Requires digital platforms to censor content deemed as disrupting the “peace”, spreading “rumours”, inciting “terrorism”

- Electronic Transactions Law (2004, 2013, 2021)

- Enables online surveillance and monitoring (eg monitor comms, track electronic transactions, collect data from ISPs and platforms, access user accounts)

Examples of Enabling Laws: International

- Cybercrime

Impact of Surveillance-Enabling Laws

- Erosion of privacy and data protection rights

- Chilling effect on freedom of expression

- Targeting of HR defenders, opposition, and minorities

- Restrictions on freedom of association & assembly

- Enabling of censorship and information control

- Algorithmic or AI-enabled discrimination

- Increased vulnerability to cybercrime due to mass data collection

No Comments