Day 2 Report

Freedom of expression and privacy | 5:00 - 6:30 UTC

👤 Prasanth Sugathan

Session details:

This session is aimed to explore the laws protecting freedom of expression across the South Asian region, while also examining the restrictions placed on this right within different legal systems. Participants will look closely at laws addressing hate speech, sedition, blasphemy, and defamation in their regional contexts. The session will further provide a brief historical overview of these laws and restrictions, tracing how they continue to surface in both offline and online spaces today.

- Broadly, what are the provisions that cover freedom of expression in international human rights law and national legislation in South Asia?

- Restrictions on FoE - what does international law say, and how does it compare to the kinds of restrictions we see in South Asia (hate speech, sedition, blasphemy, defamation and mis/disinformation etc.)?

- What kinds of laws are being passed in South Asia in relation to freedom of expression online? How does this differ from how FoE is regulated offline?

- What is the role of platforms with respect to freedom of expression online? What impact does the current policy approach towards platforms in South Asia have on FoE online? What needs to change?

Notes:

Most state governments were initially not adept on regulating online media and platforms as opposed to physical media, due to the former being created and owned by private and independent sectors. With time, governments were able to exercise their control through legislative frameworks, partnerships, and monitoring. The impact is the online space, initially promised for independent ownership and free speech, has been filtered and with privacy compromised.

By looking and comparing the perspectives of various international and national human rights laws, there is an opportunity to challenge the legislation and the disparity on the private actors/platforms’ treatment towards the Global South and the Global North. Participants can also learn from success stories of other countries.

International Human Rights Legislations

The session acknowledges that the right to Freedom of Expression (FoE) is a fundamental human right recognised internationally through these channels:

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR): Article 19 guarantees everyone the right to freedom of expression

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR): Article 19 affirms the right to FoE, which includes the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas “regardless of frontiers” and through “any other media of his choice”. This is not limited to offline/physical media, but also on online media.

- Online/Offline Parity: The Human Rights Council (HRC) has explicitly affirmed that the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, especially freedom of expression.

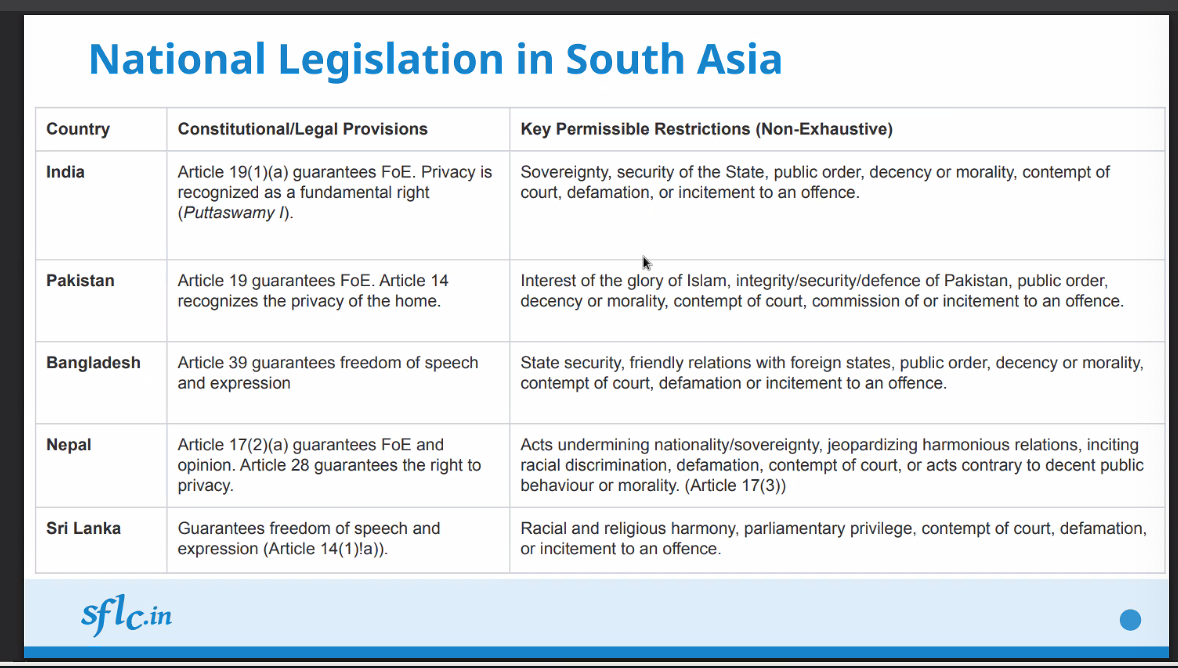

National FoE Legislations and Restrictions in South Asia:

Constitutional/legal provisions generally ensure that an individual should have freedom of speech and expression. Different states have different levels of provisions on privacy, such as:

- Nepal has provisions to guarantee the right to privacy

- India recognises that privacy is a fundamental right

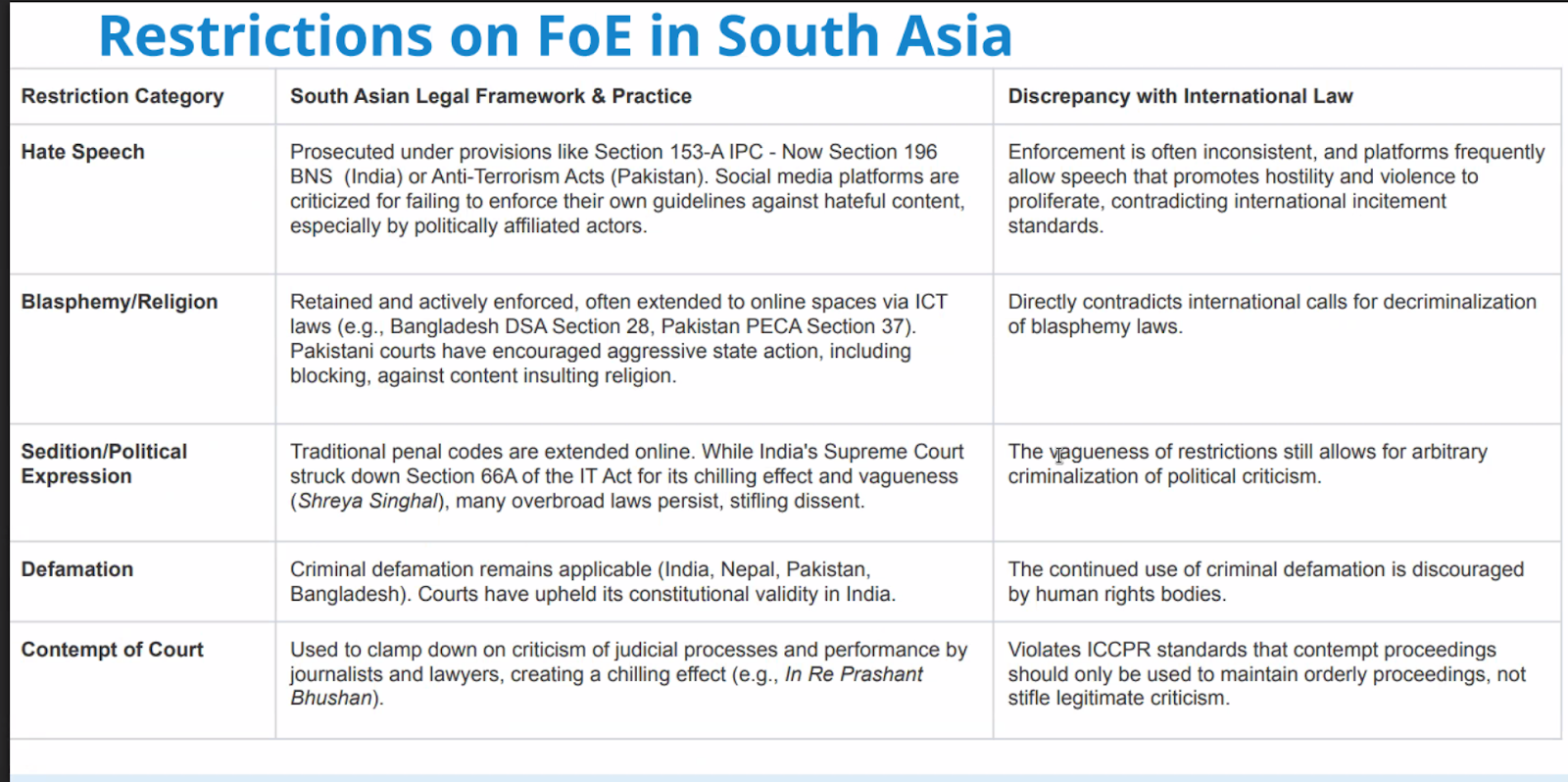

Fundamentally, FoE restrictions are meant to serve for the public good and reduce harmful behaviours, and must be proportionate and necessary, while serving legitimate aims (as per Article 19(3) of ICCPR). Unfortunately the definitions and implementations of the restrictions are disproportionate, with most often targeting voices of dissent such as journalists, individuals and whistleblowers reporting issues against any politically affiliated actors.

Such restriction categories are:

- Hate Speech - Should align with ICCPR Article 20, but most prosecuted under provisions like Section 153-A IPC, Now Section 196 BNS (India) or Anti-Terrorism Acts (Pakistan). Social media platforms are criticised for failing to enforce their own guidelines against actual hateful content made by politically affiliated actors. Enforcement is often inconsistent.

- Blasphemy/Religion - Mostly enforced against individuals and journalists, in protection of certain individuals rather than the idea of the religion itself. Examples are Bangladesh DSA Section 28, Pakistan PECA Section 37. Certain courts like Pakistani courts have encouraged aggressive state action, including blocking, against content insulting religion. Directly contradicts international calls for decriminalisation of blasphemy laws.

- Sedition/Political expression - Traditional penal codes are enforced online.

- Defamation - Vague definition on defamation content, and criminal defamation remains applicable. This is continuously discouraged by international human rights bodies who have asked for decriminalisation and imprisonment is not an appropriate penalty. Has a chilling effect on free speech.

- Contempt of Court - Used to clamp down on criticism of judicial processes and performance by journalists and lawyers. Violates ICCPR standards.

-

Content takedowns

-

Platform accountability / content moderation

-

Internet shutdowns - enforcing a disproportionate action that affects the larger public.

Such actions could cause a chilling effect of reducing free speech, instilling fear in expressing their opinions.

Three case studies in India: Safe harbour & intermediary protections

Safe harbour is mandated by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in the US.

Case 1, 2008, India: Avnish Bajaj vs State (Delhi High Court, 2008; SC, 2012).

Arrested as he landed in India for an obscene MMS sold via his own platform, baazee.com.

- Raised the question of the platform’s liability for any content posted online, even if the platform owner was not the original poster.

- Section 79 of the Information Technology Act amended in 2008, but without any discussion in the parliament.

Case 2, 2011, India: Shreya Singhal v Union of India and connected cases.

In 2011, FB and social media pages were not widely used during this time as compared to now, thus the law was imposed on various individuals for vague reasons and activities such as for liking a post that is deemed unlawful, or tracking online ecommerce activities as alibi. Struck down Section 66A IT Act for criminalising “offensive” speech, ruled unconstitutional due to ambiguous wording and could lead to chilling effect on free speech.

- Although it is intended to protect marginalised/vulnerable communities, implementation showed otherwise as there was no clarity on the provision. There was a vague understanding on the terms and conditions, including on identifying content that is deemed as unlawful, and the order to take such content down within 36 hours. It also raises the question on the platform’s accountability on considering unlawful content, or having the knowledge of doing so.

- Lawyers and CSOs reached out to the parliamentarians to look into the procedures, which prompted an MP to push a motion to annul these rules. This marked one of the rare cases where the subordinate rules and regulations on social media and online platforms were discussed and debated in the parliament. The media coverage of this debate further raised the public awareness on such issues.

- Clarified intermediary liability (Section 79 IT Act):

- Intermediaries obliged to act on takedown requests only upon court/government orders citing limits of Article 19(2).

- Overturned “notice-and-takedown by any person” regime, protecting platforms from adjudicating legality of all content

- Blocking rules found to be constitutionally valid, with the provision to hear the user’s side.

Case 3, 2021: Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules.

These rules were tabled to regulate the proliferation of misinformation on WhatsApp, especially on tracking the source of forwarded messages. Other actions include proactive filters and a 24 hour takedown for illegal content.

This coincides with the Blocking Rules (2009), in which the government has the power to request the platform (WhatsApp or Facebook, and other platforms) to take down the unlawful content. Although there is a provision to send notice to the affected party, this emergency provision is often used without any notice. The confidentiality provision also creates ambiguity in which the affected party will not receive the reasoning for the action.

In 2021, a FOSS engineer who maintains various FOSS domains and platforms, including Diaspora pod, Matrix instance Grounds filed a writ petition to challenge IT Rules 2021.

The terms used in Rule 3(1) are vague, making it uncertain on what is prohibited or permitted. Force the intermediaries to censor and restrict free speech, or lose “safe harbor” protection under the IT Act, 2000. It also impacts the right to privacy (Article 21), including the right to encryption, as it aims to introduce traceability and break end-to-end encryption.

Such rules can cause a disproportionate impact on small intermediaries or platforms, especially alternative or open source platforms run by small entities who may not have the capacity to fulfil such compliance and conduct thorough content tracing.

The writ petition is currently pending in Delhi High Court.

Blocking Instances

Mass blockings mostly occur during any protests or large dissent against politically affiliated actors or the state.

- India:

- Geopolitical blockings such as TikTok and various Chinese apps

- X handles and Youtube accounts during protests

- Entire websites, such as The Wire, Tamil news website, being taken down due to one published content

- Proton Mail - with the reasoning that there is low capacity of Indian nationality in its operations

- OTT platforms - pornographic content

- Pakistan:

- Youtube ban

- Nepal

- Telegram

Other Legal Challenges in India

- The blocking of two apps, Briar & Element, versus UOI, were brought to court for the Intermediaries Rules 2021. Briar was accused of being used by terrorism in Kashmir, which became a reason for its blocking. Element is an open-sourced p2p network that is more secure than WhatsApp.

-

- Intermediaries Rules 2021 - Challenges pending before the Delhi High Court

- Blocking Rules - Confidentiality Provision - Supreme Court. The users do not get any information regarding the take down

- Delhi High Court - Powers given to law enforcement to take down content, which finally revealed the details on the orders for the take down.

- Sahayog portal, where various agents can upload requests to take down certain content, was challenged by X at the Karnataka High Court. Unfortunately, the writ petition was dismissed with the appeal filed.

- High number of internet shutdowns in India: internetshutdowns.in

Grievance Appellate Committee (GAC)

Handles appeals from users dissatisfied with decisions made by Grievance Officers (GO) of social media and other online intermediaries. Users can reach out to GAC if they do not receive any response from the GOs, and can be challenged in court.

However, the GAC is not an independent body and is still largely governed and regulated by the state. There are no independent mechanisms and there is a huge lack of transparency in the structural and electoral processes. Some complaints are also filed once the platform responds with their defense.

Private actors and semi-private platforms’ accountability

Users can use copyright infringement as a loophole and excuse for indiscriminate take downs to navigate any unlawful content. However, platforms most often do not follow the law or the jurisdiction. For Copyright, the DMCA provision requires notification and counter notification in which the rights holder needs to produce proof of cases. Cases that are filed in a defective manner with the affected user may never get a notice. Independent journalists and smaller content creators do not have the resources to fight such takedowns.

Platforms also do not assume nor take accountability on taking down the harmful content even after filing the report on hate speech or OGBV. The platform’s own interest may go against the public good.

Organising and Mobilising on Platforms

Emerging digital spaces such as Discord, with gated servers, have become more central to grassroots mobilisation, like in Nepal, where online communities managed to drive political change through this platform. Youths were mostly moderating and mobilising, and is used as a communications channel to organise publicly.

However, such platforms have a double-edged sword on its lack of regulation and high number of users, as users are free to post any content in which some could be unlawful or incite violence against another user. The anonymity also doesn’t promise absolute security, as there could be lurking surveillance from some actors or officers. The complexity of accessing Discord or platforms that are banned, which requires certain digital and technological literacy, means it's inaccessible to all communities and creates limitations in organising and mobilising. For example, only urban youths and digital literate people knew how to access Discord via VPN.

In Bangladesh, Facebook was being used for organising.

What is one provision in the law in your country that affects free speech in your country, that you would like to be amended or deleted?

India:

- Suggests to amend Section 292 of the Penal Code on obscenity in law, noting that it is meant to protect societal morality but often results in sexual-health educators and creators being wrongly flagged as “obscene.” The definition of obscenity is often being left vague, with legitimate educational content is often flagged while harmful misogynistic content is excused as free speech.

- Suggests that the definition of obscenity should be modernised and made more inclusive, protecting free speech while still allowing appropriate regulation.

- Notes that enforcement is a separate issue that also needs improvement.

- Notes that Section 67A of the Information Technology IT Act, 2000, which punishes publications or transmissions of materials containing sexually explicit acts, is sufficient.

- Suggests abolishing Rule 31D of the IT Rules, which allows the government to issue immediate content-removal notices to intermediaries.

- Points out conflict with the Shreya Singhal judgment, with Sahyog portal, which established stronger safeguards and a defined blocking mechanism through courts.

- Emphasises that the current enforcement practices shape how “obscenity” takedowns occur, often without proper checks. The enforcement is placed on the intermediaries which often becomes compliant to the state

- Section 66(A) through judiciary measures is sufficient. Points out that India already has a court-based blocking mechanism with review committees, safeguards missing in Rule 31D.

- Warns that under state-level implementations, a single officer or telco authority may handle takedowns with no review mechanism, reducing accountability.

Bangladesh:

- Cybersecurity Ordinance Act, which allows authorities such as the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) to order content takedowns based on vague orders and broad grounds (claimed to work against national unity and economic threats.

- Widely used by the previous regime, often without any judicial order.

- Suggests to amend to require a judicial oversight.

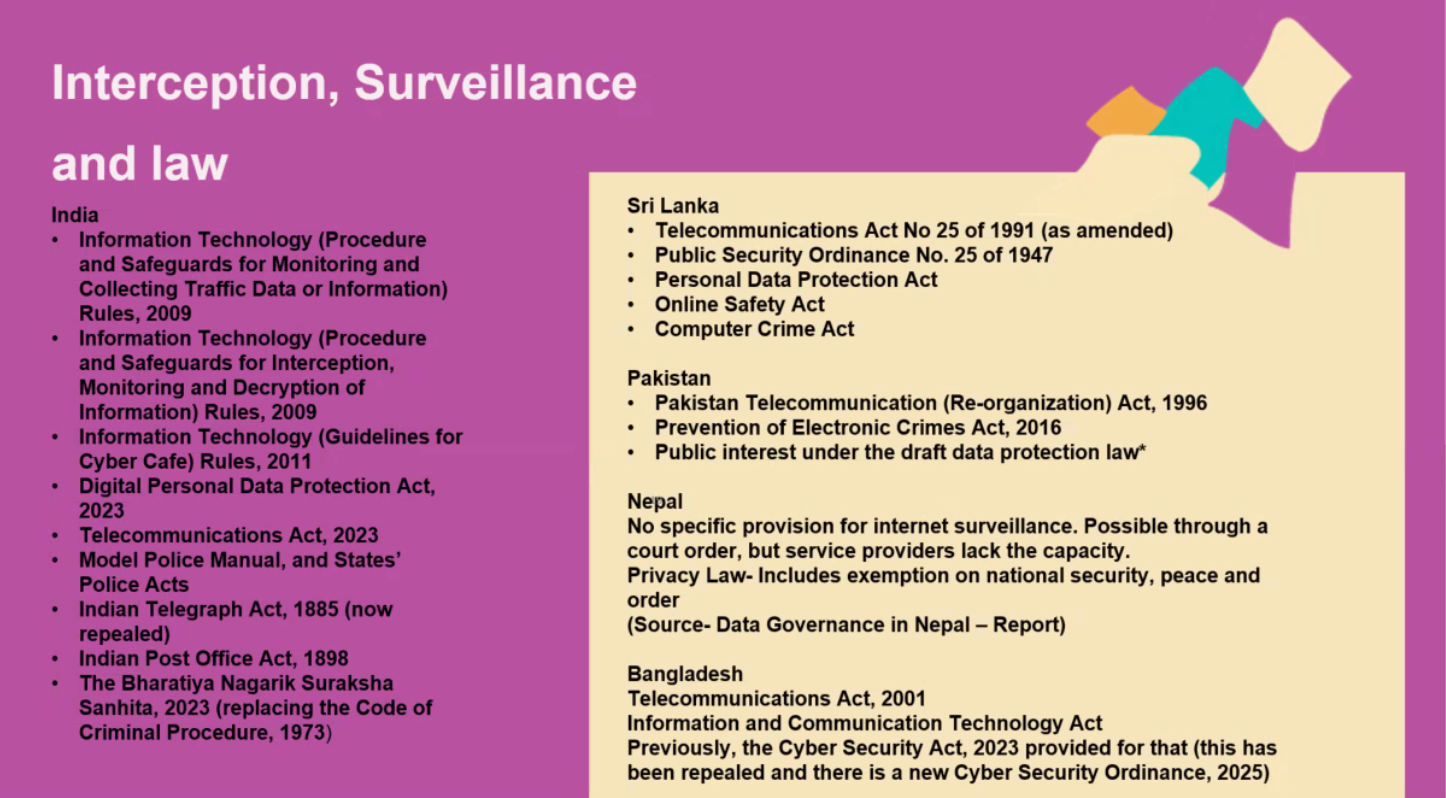

Privacy, surveillance and data protection | 7:00 - 8:30 UTC

👤 Ashwini Natesan

Session details:

In this session, participants will learn to examine the different facets of individual privacy in the digital age and the regulations designed to protect these rights. They will investigate the impact of emerging technologies on decisional privacy by considering the various forms of surveillance currently deployed in society alongside the enabling legal frameworks. This session will further focus on the rise of surveillance-related policies and their implications for the protection and promotion of digital rights.

- What is privacy in the digital age and why is it important?

- What are the ways in which the internet and other digital technologies are being used to infringe privacy and engage in surveillance?

- What are the legal and regulatory frameworks in south Asia that protect privacy, including data protection laws? What are the challenges and gaps?

- What are the ways in which legal frameworks in South Asia are being used to enable surveillance?

- What is the impact of such policies on freedom of expression, assembly and association and other rights, esp for marginalised groups?

Definitions of Privacy

Participants’ answered to what does privacy mean to them: Freedom from prying eyes; Control over my information; Unnoticed; Freedom; Being myself; Human rights; Civilised society; Non interference; Personal space; Protection

Historically, the right to privacy was first defined as the ‘the right to be let alone’ (Warren and Brandeis, 1890 Harvard Law article). For over a century, privacy law scholars labored to define the illusive concept of privacy.

The notion of ‘control’ acts as a common denominator, in which the definition of privacy is being reduced to: the control we have over information about and relating to ourselves.

- The second group highlighted ‘access’ as the essence of privacy, with a further subset called ‘secrecy’.

A Taxonomy of Privacy, Solove (2006) - identified there are lots of rights that can be classified under the umbrella of privacy, with 16 harmful activities recognised under the rubric of privacy, and further classifying them into 4 groups. The field of privacy law has expanded to encompass a broad range of Information-based harms, including from consumer manipulation to algorithmic bias.

Privacy by essence goes beyond data, as it affects the physical life. Every person should have autonomy on the information on their body, identity and physical space. For this discussion and based on the statutes and legislations available, privacy is narrowly defined under the banner of data protection.

Four Stages of Information and Data Management

‘Data Subject’ is an individual whose data is being subjected/collected. There are four stages of processes that could happen to the data:

- Information collection - What is the data being collected? Information that’s being collected to define you as an individual.

- Surveillance - intrusive

- interrogation

- Information processing- how is the information being used?

- Segregation

- Identification

- Insecurity

- Secondary use

- exclusion

- Information dissemination - where does the information get shared/dissemination? In most cases, some of the data are being shared without the knowledge of the data subject

- Breach of confidentiality

- Disclosure

- Exposure

- Increased accessibility

- Blackmail

- Appropriation

- distortion

- Invasions

- Intrusion

- Decisional interference - how we have autonomy to define the dissemination

Privacy Rights in the Digital Age

Privacy rights in the digital age are commonly understood as the right and expectation of individuals to control the collection, use, and sharing of their personal information (data, communications, conduct) in the digital realm. Not just secrecy, but autonomy and control over one’s digital self.

- Key components:

- Information privacy: protection of personal data collected and stored by entities

- Communication privacy: protection against unauthorised interception or access to personal communications (e.g. emails, messages)

- Individual privacy/identity: safeguarding one’s digital identity and online persona

Privacy is often thought of as an individual interest, and does not breach into the public good. In this sense, privacy is often pitted against other rights and freedoms more broadly “social values” such as free speech, security, innovation, efficiency and transparency.

This view is narrow and does not capture privacy as a social value - in at least two ways:

- Protects individuals for the sake of the greater social good. This leads into surveillance, in which the safeguards and transparency on its functions needed to be discussed more.

- Construct societal frameworks that distribute power more fairly and productively. Power is often associated with state and government, but current markets show that private actors and sectors are also accountable.

The right to privacy aims to preserve human dignity and autonomy, as the latter is and should be non-negotiable. The right to make decisions is currently being influenced by parties who do not have our best interests in mind.

- Prevents misuse and harm

- Identity theft and financial fraud

- Manipulation (eg through targeted disinformation)

- Cybercrime and online harassment

Contextual Understanding of Privacy

In the South Asia context, there is a lack of actual Data Protection Laws unlike in the Global North. Legislatively and culturally, privacy is not seen as a priority in most legislations, and sometimes ranked lower than other general rights. It has assumed a secondary role compared to other issues such as national security.

As noted by Anuvind, it is often framed antithetical to certain positive actions, especially crime prevention, as if "nothing to hide means nothing to fear" - but rather than centering this discourse around the "misuse" of the right to privacy, it is often discussed as a reason to not have such a 'right to privacy' in the first place.

However, the debate itself is wrong because it is mostly framed from the POV of someone else needing access to that information, rather than on the need and right for an individual to protect their own data. There is also no clarity on why other issues should be prioritised, when there is intersectionality in all cases.

Current Legal Frameworks

- Sri Lanka: Modelled after EU GDPR. Focused on how the data is being processed and transferred. An individual has the right of information, in which they also have the power to deny information requests if the request does not align with your interest.

- India: Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP) 2023, DPDP Rules 2025: defined a class called Significant Data Fiduciaries (SDFs) as the controller, who must follow stricter rules (e.g. appoint a Data Protection Officer). Individuals (‘data principles’) are granted rights such as access, correction and erasure of their data. There are heavy penalties for non-compliance

- DPDP Rules - Phased implementation

- Eg: The SDF/Controller is an individual who is in charge of managing a personal database of the company’s frequent customers. The concern is when additional storage is required, the Controller would resort to using external services such as Cloud systems offered by other providers. The Cloud system would have their own processing of the data.

- Bangladesh: Personal Data Protection Ordinance (PDPO): personal data refers to any information that can identify an individual - including names, addresses, financial information, location, health details, biometric data, and other information.

- Pakistan: no law in place when it comes to Data Protection, currently being drafted. Currently there is some pushback from the US on Pakistan’s draft that is following the EU’s GDPR framework.

- Nepal: Individual Privacy Act 2018 (“Act”) // Individual Privacy Regulation, 2020. Strives to protect the fundamental

Legal Challenges:

- Enforcement mechanism, which should ideally be an independent regulatory body with clear appointment processes.

- Broad exemptions for government agencies

- Low public awareness and digital literacy due to the culture’s conversation on privacy in general

- Existing laws do not sufficiently address risks like algorithmic bias and the need for transparency in automated decision-making. Many decisions are now automated with no human check-and-balance.

- Traditionally, GDPR is where protections are given for automated decision-making. For instance, a loan application being processed by an automated system that decides on the approval based on preset requirements without any additional nuances

- Data protection frameworks often contain large, sweeping exemptions for “national security” or “public interest”

Consent

‘Consent’ is rarely informed. Most laws have a provision that personal data can be collected, provided the individual consent to the processing of the data. But there is no real choice afforded in our terms and conditions (T&C), Thus the flaw is that consent is assumed to be a catch all process.

Behavioral experiences noted that many users do not have time to go through the T&C, and in some cases, do not have a choice in accepting the T&C if there is a strong need to use the services.

The recent example of most platforms’ terms of service that automatically entails all user content will be used to train for LLM and it is difficult to opt out, and scraped data made without consent. This further pools into the extent to how much entities, corps, individuals, groups are allowed to have access to users. Some suggestions on user-empowering consent mechanisms should look like:

- Option 1: to have a visible option to opt out from those services (when ideally there should also be a choice to opt in). If such a choice is not made available, consent is meaningless and the PDPR Act should interfere. An alternative is for the user to resist from providing any meaningful content (does not want the content to be shared for this purpose).

- Option 2: If individuals need to navigate the providers, a third party should interfere.

- Option 3: Consent should be renewed from time-to-time. Either by every update or every few years.

Surveillance by private actors and companies

Big Tech companies thrive on users’ data, evidently through targeted ads that are based on data collection and profiling. Companies collect vast amounts of user data via their digital footprint, which could be but not limited to:

These data are further integrated into the surveillance mechanism, where it is used to create detailed profiles for targeted advertising and market manipulation, often without the user’s full comprehension or meaningful consent (“consent fatigue”).

Surveillance capitalism by Harvard economist Shoshana Zuboff explains it as:

- Incursion - the user enters an area of data collection

- Habituation - the user gains a habit and does not consider the repercussions

- Adaption/Adaptation - the user agrees to the narrative

- Redirection - the user is forced to focus on the little aspects being considered without looking at it holistically

The relationship between State and Private Actors

- Surveillance capitalism is often being seen in insurance and government surveillance markets partnerships.

- Aadhar Authentication for Good Governance (Social Welfare, Innovation, Knowledge) Amendment Rules, 2025.

- Need to use data for the public good, but to be more transparent with the systems in place, ensuring that they protect and preserve rights.

- Consent, particularly, on the reliance of another entity

- India can set the standard for ethical Digital ID governance.

State Surveillance and Control

- Mass surveillance through telecom metadata collection

- Interception of communication (telecommunication)

- Social media monitoring for dissent

- Use of spyware (Recall Pegasus) and device hacking tools

- Biometric national ID systems linked to services

Case: India - Fundamental right - Justice K.S Puttaswamy (Retd) & Anr vs Union of India

- Privacy is deemed as a social construct. These observations from the Supreme Court in India pronounced privacy to be a distinct right under Article 21 of the Constitution - one that covered the body and mind, including decisions, choices, information and freedom

- Specifically mentioning that it also focused on various safeguards that should be kept in case of national identities, rejects that privacy of an individual is an elitist construct.

Impact on Freedoms (Expression, Assembly, Association)

Chilling effect on FoE:

- Suppression of Assembly and Association

- Used to identify organisers and participants of peaceful protests

- Monitor private communications related to political organising or trade union activities, thereby chilling the right to association

- In extreme cases, arbitrary detention or legal action under vaguely worded security laws

- Targeting and discrimination

- Human rights defenders or journalists

- Ethnic and religious minorities

- Women and LGBTQ+ communities

- Digital exclusion:

- Lack of safeguards, especially in the context of digital ID systems, can be used as a tool of exclusion, denying access to public services or provisions for those who cannot or will not provide extensive personal data

Can there be lawful and justified surveillance?

In the opinion of yes, there needs to be surveillance that has to go through the principles of:

- Legality - accordance with a law

- Legitimate aim that does not require an extremely invasive measure

- Suitability - adequacy

- Necessity (least restrictive measure) & proportionality stricto sensu - the harm caused to the individual by the restriction must not be excessive in relation to the benefit gained by achieving the public interest aim

- Procedural safeguards which should entails having an independent regulatory committee, that determines any rules or regulations before conducting the surveillance

Private actors can be held accountable by having a strong data protection law in place, followed by strong law enforcement and implementations. Since 2018, the instances of EU GDPR enforcement particularly against BigTech has been very encouraging in showing that an individual's access to their rights can be achieved through judiciary and other mechanisms.

Concluding Thoughts

Privacy is essential for autonomy and democratic rights. With the spread of biometric ID systems, SA faces growing concerns over surveillance. This can be mitigated by strong independent oversight, governed by a strong Data Protection Act.

Civil society should also play a bigger role in safeguarding the rights.

As an individual, one need to constantly ask:

- How is the data being shared?

- What is it being shared for?

- Where is it being shared?

- What are the protection mechanisms?

Reflection questions:

- Privacy as a right is not only about protection personal data (but, we are limited to this because of the statutes and laws we currently have)

- Surveillance is not limited to the State but also to private actors

- What are some of the use cases in your State for surveillance?

- Are the measures justified under the human rights test of legality and proportionality?

Group Discussion - privacy and surveillance: Group 3 - Case Study on Privacy and Surveillance_South Asia

- The current laws give the government too much power on what they can do, rather than on what they cannot or should not do.

- The government will push against the universities if they do not comply

No Comments